Suicide Prevention in Primary Care Settings

Introduction

There is an increasing movement to integrate behavioral health into general medical settings. One of the many reasons for this push towards integration is research on the association between suicide deaths and primary care visits, as well as the association between mental health conditions and physical health conditions.

- One study found that 45% of individuals who die by suicide visited their primary care provider in the month prior to their death. 1

- Another study found that 83% of patients who died by suicide had a primary care visit in the year prior to their death and about half did not have a mental health diagnosis. 2

- A national study found that 68% of adults with a mental illness also had at least one additional medical condition. 3

- Recent research shows that chronic health conditions such as back pain, diabetes, sleep disorders, etc., substantially increase risk for suicide. 4

Additionally, social determinants of health have been known to affect mental health and suicide risk, as mental health is significantly influenced by social, economic, and environmental conditions. Social determinants of health include economic stability, education, social and community context, health and health care, and neighborhood and built environment. Drastic changes in these areas can result in increased suicide risk (loss of job, partner/loved one, housing). Negative social determinants of health affect individual mental health as well, such as limited access to health and mental health care, poverty, unstable housing, living in a dangerous neighborhood, lack of social support, low education level, etc.

Primary care settings can make a significant difference in the lives of their patients if they strategize on how to incorporate mental health and suicide screening into their practices and pathways.

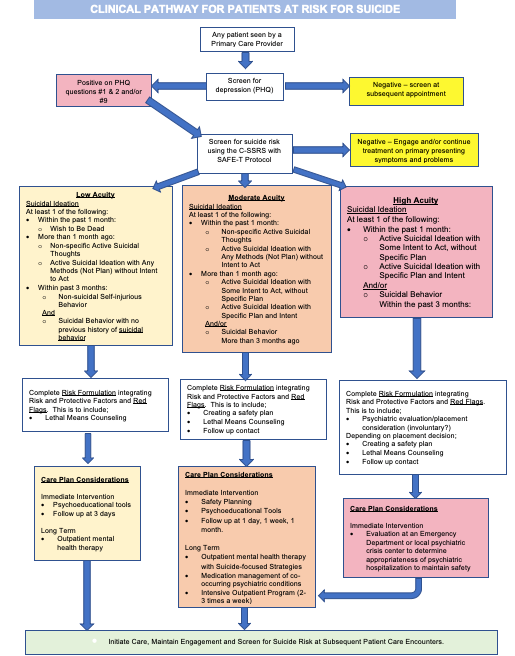

Pathway for Suicide Care in Primary Care Settings

Traditionally, treatment for mental health conditions and suicide has been a job solely for mental health professionals. As a result, screening for suicide has not been a standard practice in settings such as primary care, but that is beginning to change. In fact, studies have found that primary care providers prescribe 79% of antidepressants and see 60% of people being treated for depression in the United States. 5

Due to a number of barriers associated with access to care for suicide risk and/or crises, as well as mental health services in general, primary care settings may provide the only chance for many individuals to receive needed care and to be assessed for suicidality. To prepare primary care providers and staff for addressing suicide in their practices, here is a pathway to follow.

Text Version Clinical Pathway for Patients at Risk for Suicide

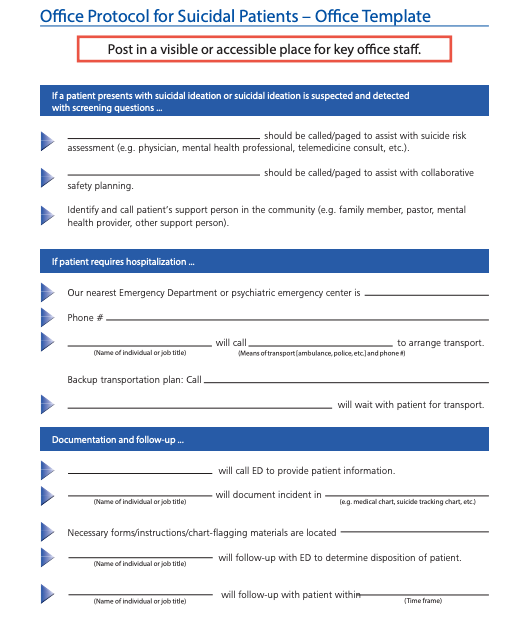

Creating an Office Protocol for Suicide Care: Incorporating suicide prevention and care into your office protocols and clinical pathways can allow you to intervene effectively without significantly disrupting the flow of patients. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center has created a Quick Start Guide which includes an Implementation Checklist for practices and an Office Protocol Development Guide.

Training

Primary care staff will be more effective, successful, and confident in suicide care if they have the training and tools to necessary. Depending on the level of knowledge and training of staff in suicide prevention and treatment, there are many resources available that can be facilitated within a practice.

Zero Suicide Training Options: Zero Suicide created a comprehensive list of training options for all types of staff in a variety of settings, including primary care. Comprehensive List of Training Options

Some specific trainings include:

Zero Suicide- Interactive, practical training for primary care professionals who screen patients for mental health and substance abuse disorders

- Prepares primary care personnel to screen patients for mental health and substance abuse disorders including suicide risk, perform brief interventions, and refer patients to treatment.

Recognizing and Responding to Suicide Risk in Primary Care

- 1 hour, online, self-paced

Includes a pocket assessment tool and reproducible patient handouts - Teaches how to integrate suicide risk assessments into routine office visits, to formulate relative risk, and to work collaboratively with patients to create treatment plans

SafeSide Primary Care

- Three 50-min group video-based sessions

Blended video and group-based learning - Brief teaching, demonstrations, and group discussion that provide a framework and practical steps for primary care.

Suicide Prevention Toolkit for Primary Care Practices: This toolkit can be used by all primary care providers. It contains tools, information, and resources to implement state-of-the art suicide prevention practices and overcome barriers to treating suicidal patients in the primary care setting. Assessment guidelines, safety plans, billing tips, sample protocols, and more.

Suicide Safer Care Webinar : Suicide Safer Care is a national initiative to train primary care and other providers in suicide identification and treatment.

Screening

Primary care providers are often asked to screen for a variety of conditions, and more recently this has included mental health conditions and suicide risk, but primary care providers often lack the capacity, skills, or confidence to incorporate these screenings into their practice. A variety of staff members can and should be involved in suicide prevention in primary care settings, from office staff and reception, to nurses and medical technicians. Annual screening reminders can be built into the practice EHR so front-desk staff or medical assistants can initiate the screening process.

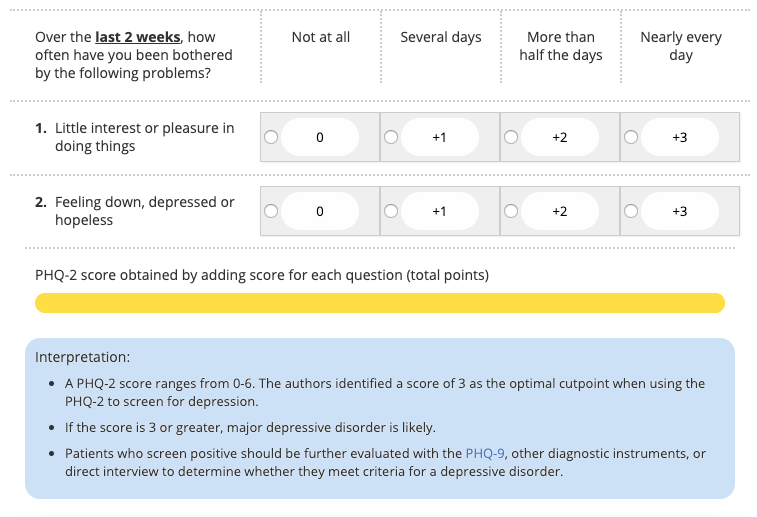

Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2): The PHQ-2 includes two questions (the first two questions from the PHQ-9) to inquire about the frequency of depressed mood over the last two weeks. This is a “first-step” approach, and all patients who screen positive should be further evaluated using the PHQ-9.

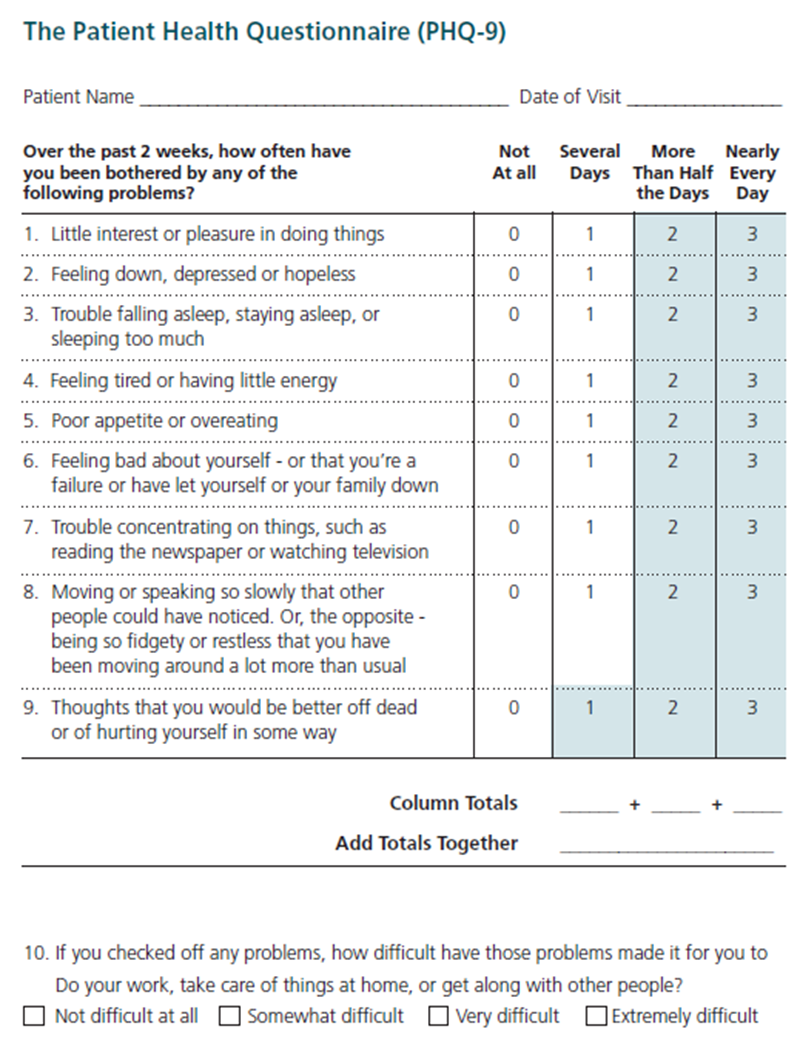

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): The PHQ-9 is a self-administered (but can be clinician-administered) screening tool for depression that has a specific question (Question #9) regarding suicide. The PHQ-9 is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The PHQ-9 is shorter than other scales, can be administered in person, by telephone, or self-administered, facilitates diagnosis, provides assessment of symptom severity, is validated in a variety of populations, and can be used in adolescents as young as 12 years old. 6 Question #9 specifically asks whether respondents have “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way.” Regardless of the total score, a positive response to question #9 warrants further risk assessment.

| Severity Levels | PHQ-9 score |

|---|---|

| Normal | 0 - 4 |

| Mild | 5 - 9 |

| Moderate | 10 - 14 |

| Moderate to severe | 15 - 19 |

| Severe | 20 - 27 |

This tool has been validated for its use in primary care settings and can be a critical tool in assisting primary care providers in diagnosing depression and suicide risk and monitoring treatment response. 7

- One study found that those who answered, “nearly every day” to question 9 on the PHQ-9 had a 4% probability of suicide attempt in the following year, a ten-fold increase compared to .04% of those who answered “not at all.” 8

- Another large study found that those who score positive on Question #9 of the PHQ-9 were 5 to 8 times more likely to attempt suicide and 3 to 11 times more likely to die by suicide within 30 days and were 2 to 4 times more likely to attempt suicide and 2 to 6 times more likely to die by suicide within a year. This increased risk persisted for two years. 9

This data shows that suicidal ideation reported on the PHQ-9 is a robust indicator of suicide attempts and deaths, demonstrating the need for providers and healthcare systems to address immediate and sustained risk for suicide in patients who screen positive on the PHQ-9. 10

PHQ-9 Follow-Up Questions

Assessment

Whether annual screening has been incorporated into a practice or screening was initiated based on patient risk and protective factors and suicide warning signs, further assessment is recommended after initial screening is complete. Here are some tools and resources for suicide risk assessment in primary care settings.

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): This tool can be used to both screen and assess suicide risk. The C-SSRS is used to identify whether the patient has thought about suicide, has acted or plans to take action, or whether they attempted suicide or plan to attempt suicide. The questionnaire begins with two questions about passive or active suicidal ideations, leading to further follow up questions based on positive responses to gauge severity. Based on the severity, resources are available with interventions for responding to the C-SSRS. This tool has an expansive evidence base and is supported by SAMHSA, the CDC, the FDA, the NIH, the WHO and many others. The tool is scored as Low, Moderate or High risk, depending on positive answers. The most concerning answers include: a recent (past month) “yes” to question 4 or 5 (see below) on ideation severity and/or any recent (past 3 months) behavior.

- An extra benefit of the C-SSRS is built-in triage guidelines. Comprehensive guide to using the scale for triage in a clinical setting.

- While the C-SSRS is unique in that it can be used by healthcare professionals, as well as friends, families, and individuals in the community, training staff to use the C-SSRS and all screening tools is important in increasing their comfort level and sense of competence. Training resources both online or in-person.

|

Ask questions that are in bold and underlined. |

Past month |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Ask Questions 1 and 2 |

YES |

NO |

|

1) Have you wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up? |

|

|

|

2) Have you had any actual thoughts of killing yourself? |

|

|

|

If YES to 2, ask questions 3, 4, 5, and 6. If NO to 2, go directly to question 6. |

||

|

3) Have you been thinking about how you might do this? e.g. “ I thought about taking an overdose but I never made a specific plan as to when where or how I would actually do it….and I would never go through with it.” |

|

|

|

4) Have you had these thoughts and had some intention of acting on them? as opposed to “ I have the thoughts but I definitely will not do anything about them.” |

|

|

|

5) Have you started to work out or worked out the details of how to kill yourself? Do you intend to carry out this plan? |

|

|

|

6) Have you ever done anything, started to do anything, or prepared to do anything to end your life? Examples: Collected pills, obtained a gun, gave away valuables, wrote a will or suicide note, took out pills but didn’t swallow any, held a gun but changed your mind or it was grabbed from your hand, went to the roof but didn’t jump; or actually took pills, tried to shoot yourself, cut yourself, tried to hang yourself, etc.

If YES, ask: Was this within the past 3 months ? |

Lifetime |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Past 3 Months |

||

|

|

|

|

Response Protocol to C-SSRS Screening

Item 1 - YELLOW - Behavioral Health Referral

Item 2 - YELLOW - Behavioral Health Referral

Item 3 - ORANGE - Behavior Health Consult (Psychiatric Nurse/Social Worker) and consider Patient Safety Precautions

Item 4 - RED - Behavioral Health Consultation and Patient Safety Precautions

Item 5 - ORANGE - Behavior Health Consult (Psychiatric Nurse/Social Worker) and consider Patient Safety Precautions

Item 6 - 3 months ago or less - RED - Behavioral Health Consultation and Patient Safety Precautions

Primary Care Pocket Care for Suicide Assessment: A brief pocket tool providing a summary of risk and protective factors for suicide, questions and scripts for use during suicide risk assessment, and a helpful decision tree for managing patients at risk for suicide.

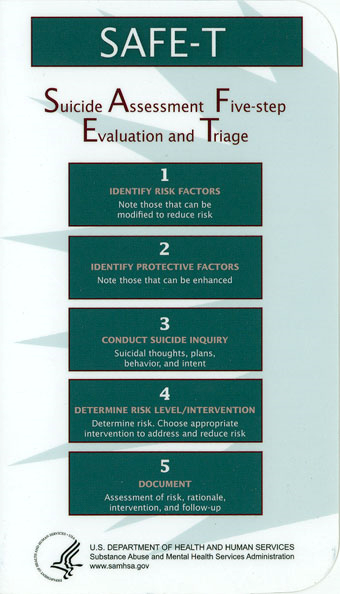

Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T): Typically found in the form of the SAFE-T Protocol Card, SAFE-T is a 5-step suicide assessment protocol used to address a patient’s level of suicide risk and suggest appropriate interventions. A detailed guide for the 5 steps below, with specific language and scripts.

Intervention

After screening and assessment are complete, the next step is to use the information gathered to inform intervention.

The Minimum WHAT (to do)

BEFORE THEY LEAVE YOUR OFFICE

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline or Crisis Text Line in their phone 1-800-273-8255 and text the word “ Hello” to 741741

- Address guns in the home and preferred method of suicide

- Give them a caring message (NowMattersNow.org)

Patient Education on Suicide Care Management: Centerstone Education Sheet: Adding a Pathway to Your Treatment Plan script that providers can use to educate patients who are at risk for suicide when they are placed on a pathway to care or suicide treatment care management plan.

Primary Care Treatment: Primary care providers can help address some of the symptoms that can contribute to suicide risk, such as anxiety and depression. In integrated care settings, a behavioral health provider can provide cognitive behavioral therapy, problem solving treatment, and/or behavioral activation. In non-integrated settings, the primary care provider can teach basic relaxation, assist in setting small behavioral goals, and provide referrals to community-based care.

Lethal Means Restriction: Anyone who is identified with any level of suicide risk, from mild to severe, should be asked about access to lethal means. Removing access to lethal means for individuals at risk for suicide should be a top priority, as research shows that over 50% of suicides are completed using a firearms.11 In Montana, firearms were used in 63% of suicides in 2016.11 Providers and patients should discuss and monitor other lethal means as well, such as access to materials for hanging/suffocation (belts, ropes, or other items) or large quantities of high-risk medications.

Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM): CALM is a workshop that helps providers identify patients who would benefit from lethal means counseling strategies, ask about access to lethal means, and work with patients and their family to reduce access.12 More information and guidance about which patients need counseling on access to lethal means

- Link to CALM workshop

- For Clinicians: Sample language and steps, goals, and things to consider when talking with patients about reducing access to lethal means.

- What Clients and Families Need to Know

- Basics of Firearms

- Firearms Laws Relevant to Lethal Means Counseling

Suicide Safety Planning: Much like action plans for physical illnesses, creating a Suicide Safety Plan can be useful for patients to refer to during moments of distress. Suicide Safety Planning is evidence-based and can help patients manage suicidal thoughts and reduce emergency rooms visits. Safety Plans are created by the patient in conjunction with a provider. Safety Plans include identification of triggers and warning signs, specific activities that can steer the patient from suicidal thoughts, contacts to be used during times of distress (community, professional, and emergency), etc.

- Training for staff on how to create a safety plan is available on the Safety Planning Intervention Site.

- Suicide Safety Planning Quick Guide

- NowMattersNow Comprehensive Safety Plan Guide

- Safety Plan pdf

- My3 is a mobile application that helps users define a network and create a plan to stay safe

Mental Health Partnerships and Referrals: With known associations between suicide risk and mental health conditions, some patients in your care with risk for suicide will need mental health care as well. One of the reasons for addressing suicide in primary care settings is a lack of access to mental health services for many patients (financial, cultural, geographic). Practices with integrated behavioral health are able to use members of their own teams to provide brief, treat to target interventions. Integrated behavioral health providers can provide counseling, check in calls between appointments, partner with primary care providers in assessing medication adherence and effectiveness. Practices without integrated behavioral health care can build relationships with therapists in the community who are not only willing to see and treat patients who are struggling but are also willing to coordinate their care with primary care provider. For patients experiencing suicidal thoughts, this coordination of care with community-based providers is critical and should be part of the referral agreement from primary care.

Further Resources

- Suicide Prevention Toolkit for Primary Care Practices

- Suicide Care Pathway: Linking Screening and Assessment to Brief Intervention

References

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12042175/

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11606-014-2767-3

- Sarah Goodell, Benjamin G. Druss, and Elizabeth Reisinger Walker, “Mental disorders and medical comorbidity,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, February 2011.

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/06/170612094032.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3670434/#:~: text=The%20bulk%20of%20mental%20health,little%20support%20from%20specialist%20services.

- https://billingsgazette.com/opinion/editorial/gazette-opinion-montana-prescription-to-stop-suicide/article_4c796b7f-694b-543f-bfb2-e3bfe944a342.html

- https://aims.uw.edu/resource-library/phq-9-depression-scale

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18186994/?dopt=Abstract

- https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ps.201200587

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5412508/

- https://sprc.org/about-suicide/scope-of-the-problem/means-of-suicide/

- https://sprc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2016-Montana-Suicide-Mortality-Review-Report.pdf

- https://zerosuicidetraining.edc.org/enrol/index.php?id=20